Jaw Joint Problems and their Effects

Jaw joint problems affect how well your jaw works. Your jaw joint is called the temporomandibular joint (TMJ). Problems with your TMJ can make your jaw feel sore and can cause headaches and ear pain too. TMJ problems usually get better on their own.

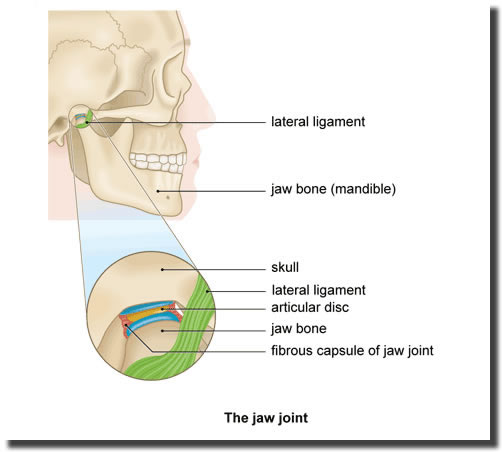

Your jaw joint (temporomandibular joint or TMJ) connects your lower jaw (mandible) to your skull. It allows your mouth to open and close so you can speak and chew. Lots of muscles and ligaments help your jaw move up and down, from side to side, and backwards and forwards.

If you have a problem with your jaw joint or the muscles around it, this is usually called temporomandibular jaw disorder.

You can get problems with your jaw at any age, but it’s most likely to happen when you’re between 20 and 40.Doctors don’t know exactly what causes jaw joint problems, and why some people are more likely than others to get problems. But you may be more likely to get jaw joint problems if you:

Stress, depression and anxiety don’t directly cause jaw joint problems, but they may make jaw joint problems worse. This is because you may be more likely to grind your teeth. For example, during times of stress, you might grind your teeth at night or while you’re concentrating without realising. But, if you grind your teeth, it doesn’t necessarily mean you’ll have jaw joint problems.

Some people with jaw joint problems have other chronic health conditions (conditions that last longer than three months), such as:

These chronic conditions may affect how well your muscles and joints work or how your body reacts to pain. Other things that can affect your jaw joint include the following.

If you have a problem with your jaw joint, you may:

You may find that your jaw pain gets worse during the day or when you chew or talk. You may be able to manage these symptoms at home and they often get better on their own. But if you’re worried about the pain or your symptoms are getting worse, make an appointment with your dentist to find out if treatment could help.

If your jaw hurts or doesn’t feel right, see your dentist. They’ll ask about your symptoms and if you have any health problems or long-term medical conditions. Your dentist will then check your head, neck, face and jaw.

They may:

Your dentist can usually diagnose jaw joint problems just by examining your jaw. But sometimes they may want to check if part of your jaw joint is out of place or if you have any signs of arthritis. They may refer you to a specialist doctor such as an oral and maxillofacial surgeon. You may need to have some tests and scans to check your jaw joint, including:

Jaw joint problems often get better on their own after a few months or so. There are lots of things you can do to ease your symptoms.

If self-help measures don’t ease your symptoms, your dentist or doctor may suggest you try some medicines or other treatments. The best treatment for you will depend on what’s causing your jaw joint problems and how bad they are.

A Bite Guard

If your jaw joint problem is caused by clenching your jaw or grinding your teeth, your dentist may suggest you wear a bite guard (bite splint), usually at night. This plastic cover fits over your upper or lower teeth and stops them coming into contact with each other. A bite guard may ease your jaw pain but it may not help you to move your jaw more easily.

Physiotherapy

Physiotherapy may help to ease your symptoms. Jaw-stretching TMJ exercises, massage and changing your posture may help to relax your jaw muscles. For more information, see our FAQ below: Can TMJ exercises help my jaw joint problems?

Medicines

Over-the-counter painkillers, such as paracetamol or ibuprofen, may help to ease any pain. You can buy these from your local pharmacy. Your pharmacist can help you choose the right one for you. You may be able to take these as tablets. Or you may be able to put a gel containing an anti-inflammatory painkiller, such as ibuprofen, directly onto your jaw.

If you have a lot of TMJ jaw pain, your dentist or doctor may prescribe some stronger medicines. These include the following.

Surgery

Most people don’t need surgery for jaw joint problems. But if other treatments haven’t worked for you, your dentist may refer you to a specialist. You may see an oral and maxillofacial surgeon or an ear, nose, and throat specialist. Your specialist may suggest surgery if you’re in a lot of pain and your jaw joint is affecting your daily life.

Your surgeon may suggest:

It’s important to discuss the risks and benefits of surgery with your surgeon to see if it’s the right option for you.

Complementary Therapies

Some people find acupuncture helps to ease their jaw joint pain. But it doesn’t work for everyone and may only last for a short time. Experts need to do more clinical trials to see how well acupuncture works for jaw pain before they can recommend it.

Download the Patient Information Leaflet

TMJ and Jaw Joint Problems Information Sheet

All the information you neeed. Click to download to your computer or mobile device.

Case Study: Joint Related (Arthrogenic) Jaw Pain

James is a 41-year-old teacher who began experiencing clicking sounds in his jaw, pain when chewing, and difficulty opening his mouth fully. Over time, his symptoms worsened. He noticed his jaw would “lock” occasionally, especially when yawning, and he had to move it a certain way to get it to open properly again.

His symptoms included:

James initially thought it was just stress or teeth grinding, but when the pain started affecting his ability to eat and speak, he sought help.

After seeing a dentist and being referred to a specialist in oral and maxillofacial surgery, James underwent an MRI scan. The scan showed:

This type of TMJ disorder is called arthrogenic, meaning the problem originates from inside the joint itself, not just from the muscles. The disc that cushions the joint was no longer in the right place, leading to joint friction, pain, and restricted motion.

James’s care team developed a step-by-step treatment plan, starting with conservative methods before considering surgery.

Occlusal Splint (Mouth Guard)

James was fitted with a custom night guard to reduce pressure on the TMJ. This helped prevent teeth grinding and gave the joint space to relax overnight.

Physiotherapy

He began TMJ-focused physiotherapy, including:

These methods helped reduce his pain but did not fully restore his jaw opening or eliminate the joint noise.

Surgery

Because James continued to have persistent joint pain and restricted opening, his surgeon recommended moving forward with minimally invasive arthroscopic TMJ surgery.

Arthroscopic Surgery:

A small camera was inserted into the joint space, allowing the surgeon to wash out the joint, remove debris, and try to reposition the disc. This procedure was done under general anaesthetic and required only small incisions.

In James’s case, the disc could not be repositioned, and after a few months, symptoms returned. He later underwent open joint surgery, where the surgeon had better access to repair the joint directly.

After open joint surgery:

"It was frustrating not being able to eat a sandwich or yawn without pain. I didn’t realize how much the jaw joint affects daily life. The journey wasn’t easy, but with the right support and treatment, I got my life back."

Case Study: Living with TMJ Pain

Sarah is a 34-year-old marketing executive who started experiencing jaw pain and tightness around her temples and cheeks about a year ago. She noticed it was worse in the mornings, after long meetings, or during stressful periods at work. She often caught herself clenching her jaw during the day and grinding her teeth at night—something her partner pointed out after hearing it in her sleep.

Her symptoms included:

Despite trying over-the-counter pain relief, warm compresses, and even changing her pillow, nothing seemed to work long-term.

After visiting her dentist and being referred to a specialist, examination and an MRI scan was performed.

Sarah was diagnosed with muscular temporomandibular joint disorder (TMD)—a type of TMJ disorder caused primarily by muscle tension rather than damage inside the jaw joint itself.

Unlike TMJ disorders that involve the joint structure (such as disc displacement or arthritis), Sarah’s pain was due to overactive and strained jaw muscles, particularly the masseter and temporalis muscles, from long-term clenching and grinding.

Sarah’s care team recommended a non-surgical, step-by-step approach to managing her symptoms.

Physiotherapy

She started with jaw-focused physiotherapy, including:

Within a few weeks, Sarah noticed some improvement, especially when combined with stress reduction and avoiding chewy foods.

Botox Injection

Because her muscles were still very tight and sore despite therapy, her clinician recommended Botox injections into her masseter and temporalis muscles.

Botox works by temporarily relaxing overactive muscles, reducing tension, and preventing involuntary clenching. The procedure was quick, done in the clinic, and relatively painless.

Within two weeks of Botox treatment, Sarah reported:

"I never realized how much stress was affecting my jaw. Once I understood that the pain was muscle-related, everything changed. Physiotherapy taught me how to care for my jaw, and Botox gave me the relief I didn’t think was possible."